Ranolazine: Minimize Adverse Effects With Expert Guidance

Ranolazine, a medication primarily used to treat chronic angina, has been a cornerstone in cardiovascular therapy due to its unique mechanism of action that inhibits the late sodium current in cardiac myocytes, thereby reducing intracellular sodium and calcium overload seen in ischemic conditions. This distinctive action helps in alleviating symptoms of angina without significantly affecting heart rate or blood pressure, setting it apart from traditional agents like beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers. However, as with any pharmacological intervention, the potential for adverse effects exists, and it is crucial to approach its use with a comprehensive understanding to minimize risks and maximize therapeutic benefits.

Understanding Ranolazine’s Pharmacological Profile

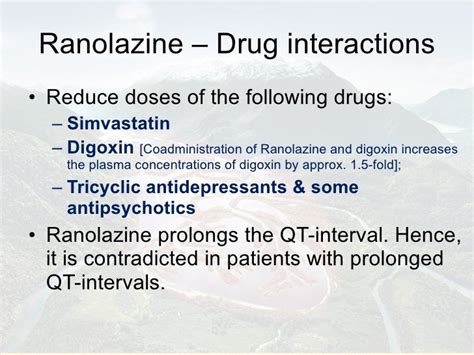

To effectively manage and minimize the adverse effects associated with ranolazine, it’s essential to grasp its pharmacological profile. Ranolazine is known for its high bioavailability when taken orally, with extensive distribution into the body tissues. It undergoes significant hepatic metabolism, primarily through the CYP3A4 and to a lesser extent CYP2D6 enzymes, which can lead to drug interactions, particularly with inhibitors or inducers of these enzymes. The drug’s elimination half-life allows for twice-daily dosing, contributing to its ease of use and compliance. Understanding these pharmacokinetic properties can help in predicting and managing potential adverse effects.

Common Adverse Effects of Ranolazine

While ranolazine is generally well-tolerated, especially in comparison to other antianginal medications, several adverse effects have been reported. These include:

- Gastrointestinal symptoms: Constipation is one of the most commonly reported side effects, likely due to ranolazine’s effect on sodium channels in the gut. Other gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea and vomiting can also occur but are less frequent.

- Central Nervous System (CNS) effects: Headache, dizziness, and tremor have been noted in some patients. These effects are generally mild and may be related to the drug’s action on sodium channels in the CNS.

- Cardiovascular effects: Despite its primary use in treating cardiovascular conditions, ranolazine can also cause some cardiovascular adverse effects, though these are less common. These may include orthostatic hypotension, palpitations, and in rare cases, QT interval prolongation, which can predispose to serious arrhythmias like Torsades de Pointes.

Strategies for Minimizing Adverse Effects

Given the unique profile of ranolazine and the potential for adverse effects, several strategies can be employed to minimize risks:

- Dose Titration: Starting with a lower dose and gradually increasing as needed and tolerated can help reduce the incidence of adverse effects. This approach allows the patient’s body to adjust to the medication, potentially reducing the severity of side effects.

- Monitoring for Interactions: Given ranolazine’s metabolism by CYP3A4 and CYP2D6, careful monitoring for potential drug interactions is crucial. Co-administration with strong inhibitors or inducers of these enzymes can significantly affect ranolazine plasma levels, either leading to increased risk of adverse effects or reduced efficacy.

- Patient Education: Educating patients on the potential side effects and the importance of adhering to the prescribed regimen can enhance safety. This includes advising patients to report any new or worsening symptoms to their healthcare provider promptly.

- Regular Follow-Up: Regular clinical follow-up allows for the early detection of adverse effects and the adjustment of the treatment plan as necessary. This proactive approach can help in minimizing the impact of side effects on the patient’s quality of life.

Expert Guidance and Individualized Care

The key to minimizing adverse effects while maximizing the therapeutic benefits of ranolazine lies in expert guidance and individualized patient care. Healthcare providers must consider the patient’s overall clinical profile, including comorbid conditions, other medications, and specific cardiovascular risk factors, when initiating ranolazine therapy. By adopting a personalized approach to treatment and maintaining open communication with patients, healthcare providers can tailor the use of ranolazine to meet the unique needs of each patient, thereby optimizing outcomes and safety.

Future Directions and Emerging Therapies

As the landscape of cardiovascular therapy continues to evolve, the role of ranolazine and its potential combination with other agents or novel therapeutic approaches will be an area of ongoing research. The development of new pharmacological entities that build upon the unique mechanism of action of ranolazine, or that offer improved safety and efficacy profiles, will be crucial in advancing the management of chronic angina and related conditions.

Conclusion

Ranolazine represents a valuable option in the management of chronic angina, offering a unique mechanism of action that distinguishes it from other antianginal agents. By understanding its pharmacological profile, recognizing potential adverse effects, and employing strategies for their minimization, healthcare providers can effectively utilize ranolazine to improve patient outcomes. As with any medication, a balanced approach that considers both the benefits and the risks is essential for optimalpatient care.

What are the most common side effects of ranolazine?

+The most common side effects of ranolazine include constipation, nausea, headache, and dizziness. These effects are generally mild and may diminish over time as the body adjusts to the medication.

Can ranolazine be used in patients with kidney disease?

+Ranolazine can be used in patients with kidney disease, but dosage adjustments may be necessary depending on the severity of the renal impairment. It’s essential to consult with a healthcare provider for personalized guidance.

How does ranolazine compare to other medications for chronic angina?

+Ranolazine offers a unique benefit in the treatment of chronic angina by not significantly lowering heart rate or blood pressure at therapeutic doses, which can be advantageous in certain patient populations, such as those with bronchospastic disease or those who cannot tolerate traditional agents due to hypotension or bradycardia.