Pain Level Scale

The concept of pain is complex and multifaceted, making it challenging to quantify and measure. However, to better understand and manage pain, various pain level scales have been developed. These scales aim to provide a standardized way to assess and communicate the intensity and characteristics of pain. In this article, we will delve into the world of pain level scales, exploring their development, types, applications, and limitations.

Pain is a universal human experience, and its impact on individuals and society is significant. According to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), pain affects over 1.5 billion people worldwide, resulting in substantial economic, social, and personal burdens. The IASP defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage.” This definition highlights the subjective nature of pain, which can vary greatly from person to person.

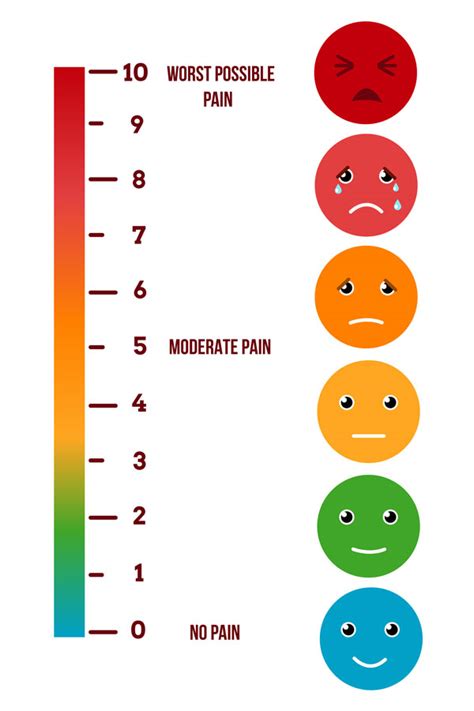

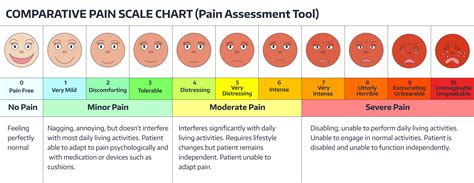

To address the complexity of pain, healthcare professionals have developed various pain level scales. These scales typically range from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 representing the worst possible pain. The most commonly used pain level scales include:

- Numeric Rating Scale (NRS): This is a simple, 11-point scale where patients rate their pain from 0 to 10.

- Visual Analog Scale (VAS): This scale consists of a continuous line, usually 10 cm long, with “no pain” at one end and “worst possible pain” at the other.

- Faces Pain Scale (FPS): This scale features a series of faces with different expressions, ranging from a smiling face (no pain) to a crying face (worst possible pain).

- McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ): This comprehensive questionnaire assesses the location, quality, and intensity of pain, as well as its impact on daily activities.

These pain level scales have been widely adopted in clinical practice, research, and patient care. They provide a valuable tool for healthcare professionals to:

- Assess pain intensity: By using a standardized scale, healthcare professionals can quantify pain and monitor its progression or regression over time.

- Evaluate treatment effectiveness: Pain level scales help determine the efficacy of treatments, such as medications, therapies, or interventions.

- Communicate with patients: Pain level scales facilitate patient-provider communication, ensuring that patients’ concerns and needs are addressed.

- Inform research and policy: Data from pain level scales contribute to a better understanding of pain and its management, ultimately shaping research, policy, and clinical practice.

Despite their widespread use, pain level scales have limitations. Some of these limitations include:

- Subjectivity: Pain is a subjective experience, and individuals may perceive and report pain differently.

- Cultural and linguistic barriers: Pain level scales may not be universally applicable, as cultural and linguistic differences can affect how pain is perceived and communicated.

- Emotional and psychological factors: Pain can be influenced by emotional and psychological factors, such as anxiety, depression, or stress, which may not be fully captured by pain level scales.

To address these limitations, researchers and clinicians are exploring new methods to assess and manage pain. These include:

- Multidimensional pain assessment tools: These tools evaluate multiple aspects of pain, such as intensity, quality, and impact on daily activities.

- Pain biomarkers: Researchers are investigating biological markers, such as genetic or neuroimaging markers, to objectively measure pain.

- Personalized pain management: This approach involves tailoring pain management strategies to individual patients’ needs, taking into account their unique characteristics, medical history, and preferences.

In conclusion, pain level scales are valuable tools for assessing and managing pain. While they have limitations, they provide a standardized way to communicate and quantify pain, facilitating patient care, research, and policy development. As our understanding of pain and its complexities evolves, it is essential to continue developing and refining pain assessment tools to improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

What is the most commonly used pain level scale?

+The Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) is the most commonly used pain level scale, which ranges from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 representing the worst possible pain.

What are the limitations of pain level scales?

+Pain level scales have limitations, including subjectivity, cultural and linguistic barriers, and emotional and psychological factors that may not be fully captured by the scales.

What is the importance of pain level scales in patient care?

+Pain level scales provide a valuable tool for healthcare professionals to assess pain intensity, evaluate treatment effectiveness, communicate with patients, and inform research and policy, ultimately improving patient outcomes and quality of life.

In the pursuit of better pain management, it is essential to recognize the complexities and nuances of pain. By acknowledging the limitations of pain level scales and continuing to develop and refine pain assessment tools, we can work towards creating more effective and personalized pain management strategies. As research and clinical practice evolve, it is crucial to prioritize patient-centered care, addressing the unique needs and experiences of individuals with pain. Ultimately, this multifaceted approach will help alleviate the burden of pain, improving the lives of millions of people worldwide.

The journey towards optimal pain management is ongoing, and it requires a collaborative effort from healthcare professionals, researchers, and patients. By working together and embracing the complexities of pain, we can create a future where pain is better understood, managed, and alleviated, improving the quality of life for individuals and families affected by this universal human experience.

Steps to Improve Pain Management

- Recognize the complexities and nuances of pain, acknowledging its subjective nature and the impact of emotional and psychological factors.

- Develop and refine pain assessment tools, incorporating multidimensional approaches and personalized strategies.

- Prioritize patient-centered care, addressing the unique needs and experiences of individuals with pain.

- Stay updated on the latest research and clinical practice guidelines, incorporating evidence-based approaches into pain management strategies.